Impatient public encourages fake news

October 18, 2019

If you watch the news, the term “fake news” has probably been rattled off to you by some sort of reporter who has a quota to achieve. Every now and then a quote is misplaced, misused, or misunderstood. Lines are twisted to make people appear unethical or even villainous. Headlines create false stories before the real ones have been typed up.

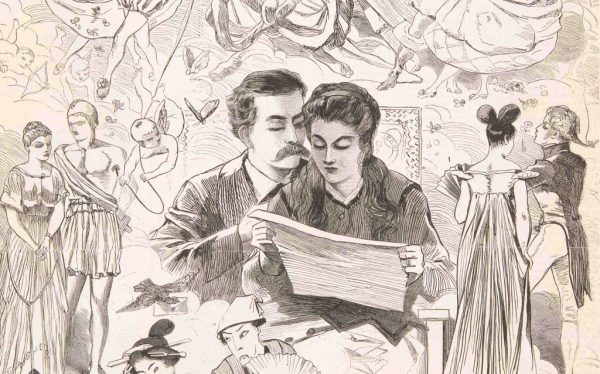

“Yellow Journalism,” a term dating back to the 1800s essentially meaning fake news, prompted the United States into entering the Spanish War. Journalism is a powerful weapon that can challenge political systems and reshape societies, and in the wrong hands, can pit an entire nation against itself.

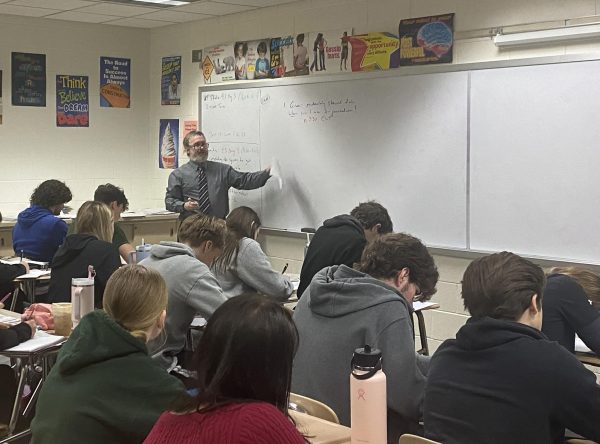

“It’s people not doing their homework and then when people do, do their homework, then the story changes,” Jon Hill, English teacher, said.

Fake news dates to the 15th and 16th centuries when printers “would crank out pamphlets, or newspapers, offering detailed accounts of monstrous beasts or unusual occurrences,” according to The Economist. Stories of a monster with goat legs, a human body, seven arms and seven heads spread like wildfire, and like now, printers would argue that their primary job is “providing a means of distribution and were not responsible for ensuring accuracy.” In 2019 the internet has taken up the same excuse.

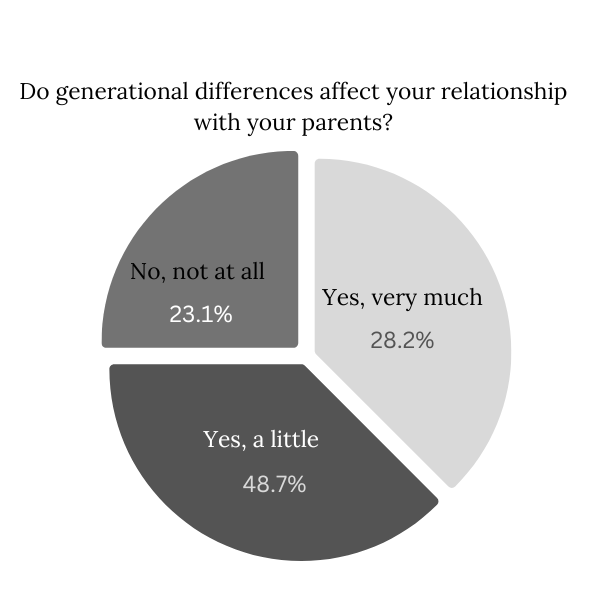

A survey done by Pew Research Center showed that 23 percent of American adults have shared fake news whether they knew they were or not. In a 2017 article published on the National Bureau of Economic Research website, following the 2016 election, 14 percent of Americans called social media their “most important source.”

“The first time I noticed when the news went downhill is when I saw a legitimate reputable news website that headlines ‘Lindsay Lohan enters Rehab again.’ And that’s when I knew entertainment news entered regular news, and that’s when I knew there was no going back,” John Smith, social studies teacher, said.

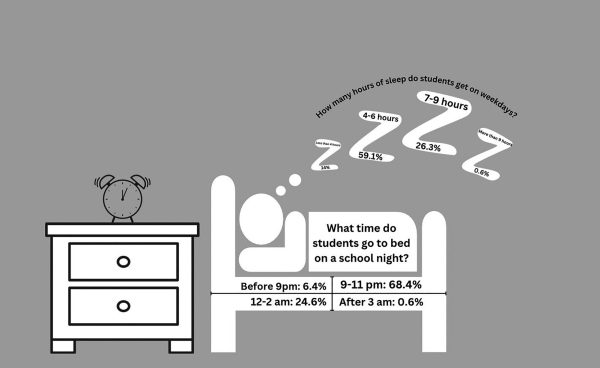

Slowly, entertainment has crept its way into news channels to keep up with the demand and low attention span that human beings have now developed, so journalists are forced to crunch out half-reported news. A research study by Microsoft Corp found that the human attention span dropped from twelve seconds in 2000 to eight seconds in 2015.

A team of researchers from Technical University of Berlin and the Technical University of Denmark, specifically the study’s co-author Sune Lehmann, found that because of low attention span, it is easier for journalist to spread fake news and “manipulate”.

“Who’s willing to actually sit through all of that information that gets them heated up and angry when it’s their relax time and they have the option to go to another station? But I find that if you don’t it’s hard to understand other people,” Scott Nissley, math teacher, said.

Preventing fake news poses challenges, however. On March 18, Vladimir Putin made it illegal for “individuals and online media [to spread] what Russia calls ‘fake news’ and information which ‘disrespects’ the state” cited by National Public Radio. The United States could not place this type of regulation on their citizens because of the First Amendment. Regulation by the government would not be necessary if media took up new tactics to prove unbiases in news.

“I would love to see a news cite that cuts and admits the spin. Down the left-hand side of the screen it shows you what the liberals are saying, down the right hand-side, it shows you what the conservatives are saying and down the middle of the screen it shows you the undisputed facts,” Smith, said.